When it comes to energy upgrades, there’s nothing like pain in the pocketbook to encourage you to take household energy efficiency seriously. And while there’s no shortage of people writing articles that tell you how to use less energy in your home, most of this advice is written by people who have never actually done anything they write about.

The ideas are not necessarily wrong, but most are too basic and won’t make much of a difference. The list below is different. It’s specific and based on experiences I’ve had personally or my consulting clients and I have had together.

#1. Upgrade loose-fill attic insulation

Sounds lame and boring, but more loose fill often yields the best bang for the buck when it comes to energy upgrades. And isn’t it just like life to offer the biggest benefit for the most boring upgrades?

How many inches of attic insulation are in your building now? How many should there be? Measure what you’ve got in several places, average them, then plan to add enough new fibre to bring the total depth up to at least 16 inches (40 centimetres) or R-49, and more is better.

Fibreglass loose fill costs a bit more than cellulose, but resists settling better. The cost of upgrading a typical attic with blown-in insulation is less than $1,000, and this delivers hundreds of dollars of savings each year.

Possible savings: 10 to 80 per cent depending on the current state of your attic.

#2. Seal the attic before insulating

A huge amount of heat goes up and out of houses through the attic unnecessarily each winter, often forming troublesome ice dams as it does. And since most attics are ventilated, attic leaks draw warm, indoor air upwards, right through batts or loose fill.

If you’re dealing with a new attic, or a sparsely insulated one, take the time to air-seal plumbing stacks, ceiling light boxes, holes for wiring and the gaps around exhaust fan housings using low expansion foam. Also, weatherstrip the attic access hatch as diligently as you would any other opening to the outdoors. From a thermal point of view, that’s exactly what it is.

The attic hatch below is from a house I did some work in and it was not insulated on top. This let the inner face of the hatch get cold in winter, and since this house had humidity that was way too high during cold months, moisture condensed onto the cold hatch, triggering the mould growth you see.

Possible savings: Five to 10 per cent.

#3. Build with SIPs

According to a handful of studies, homes built with structural insulated panels (SIPs) use roughly half the energy of an identical 2×6 stick-frame house built to code, all else being equal. This is massive.

Why are SIPs so much more energy efficient? They provide a more continuous layer of insulation than a stud wall, with much fewer areas of thermal bridging and no chance of insulation settling over time. SIPs add three or four per cent to total building costs but yield serious energy savings forever after that.

They make especially good sense for roofs with cathedral ceilings. SIPs free you from monkeying around installing insulation over your head and they guarantee against internal frost buildup and ceiling leaks so common with framed cathedral ceilings.

The photo below is of a small house I designed and oversaw construction on, built entirely with SIPs — walls and roof.

Possible savings: 50 per cent compared with code-built, stick-frame construction.

#4. Warm up an over-garage bedroom floor

The ubiquitous two-storey home with a bedroom over the garage freezes more feet every year than any other housing detail where I live. If you’re redoing the finished floor in a cold bedroom anyway, put a layer of extruded polystyrene foam down on the subfloor — one inch is good, two inches is better — with a new, ½-inch-thick plywood subfloor on top.

Extruded polystyrene foam is dense enough that wooden strapping isn’t necessary. Drive deck screws down through the new plywood and the foam, into the underlying floor joists. If foam doesn’t make your toes warm enough, it makes sense to boost heating capacity with electric, in-floor heating mats under the new finished floor.

While it’s true that electricity isn’t the cheapest way to heat, the amount of heat required to warm the floor of a bedroom is small. Putting that heat right at floor level delivers the most comfort per kilowatt-hour.

The photo below shows Schluter’s DITRA-HEAT system going down on a project of mine. The orange plastic uncoupling membrane gets glued down with thinset tile mortar, the grey heating cables get snapped between the raised circular protrusions, then tiles can be installed over that.

Possible savings: Five to 10 per cent. This approach may cost you a bit, but greater comfort is the main goal.

#5. Spray foam stud walls

Spray foam is much more expensive than batts for insulating stud frame walls, but the energy saved over the long haul makes the difference in cost an investment, not an expense. You can sub-contract spray foam application in more and more areas, or you can use disposable spray foam systems for smaller, onsite application.

One option I’ve used is Tiger Foam, but there are certainly others. DIY foam kits come as a disposable, two-tank system, with hoses, a spray gun and a bunch of replaceable spray tips. Although this kind of foam requires a warm application environment, this stuff hardens in less than a minute.

Possible savings: 50 per cent compared to a fibre-insulated equivalent of the same R value.

#6. Foam rim joists

Spray foam is one of the only practical ways to seal and insulate rim joists around the perimeter of a floor frame. Batts are a waste of time here because it’s impossible to create a sealed vapour barrier around all those joists.

Just pull back existing batts and see the black mould for yourself. Warm air filters through the insulation and cools against the rim joist, forming liquid water and fostering mould growth behind the batts.

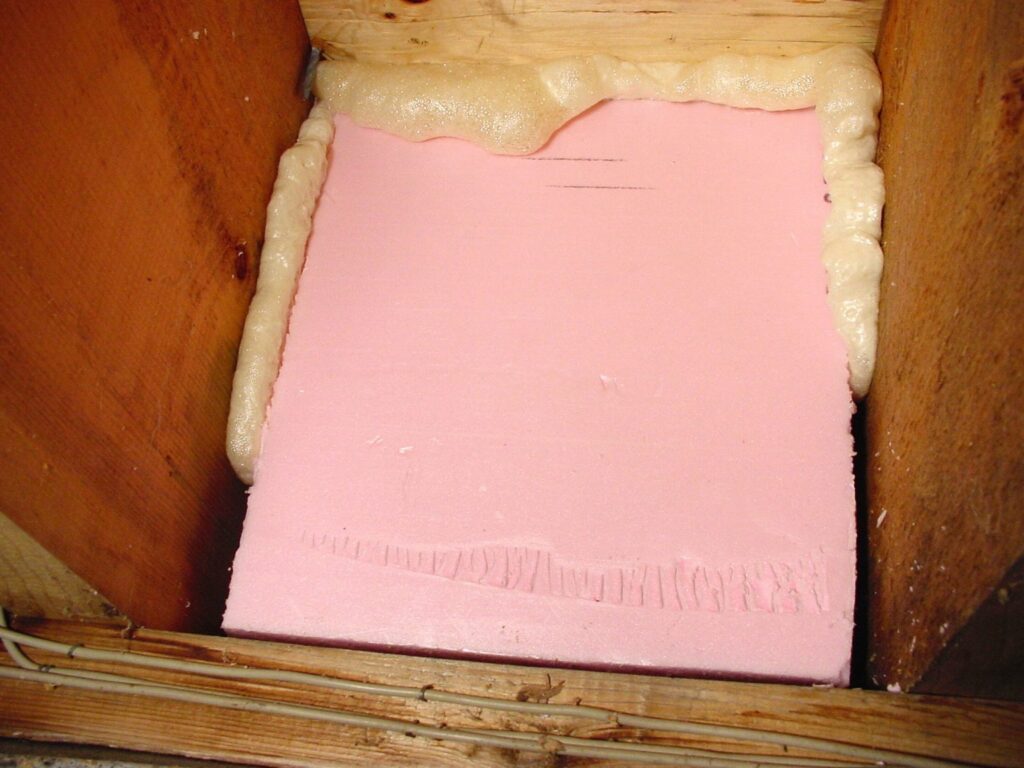

If you’d rather not bother with a spray foam contractor or spray-it-yourself tanks, cut pieces of two-inch-thick extruded polystyrene to fit between the joists with a ¾-inch gap all around. Stick the foam in place with construction adhesive, then use a small can of spray foam to fill the gaps and air-seal the edges.

Here’s a photo of some foam I’m installing, with spray foam applied around the perimeter to seal out the inside air.

Possible savings: Probably less than five per cent, but the advantage is freedom from mould growth.

#7. Inject slow-rise foam into wall cavities

Plenty of older homes have hollow wall cavities, and many can’t be insulated with blown-in, loose fill insulation because the cavities aren’t large enough or open enough. Slow-rise foam injections offer an option for insulating exterior walls that would otherwise require foam cladding from the outside or inside.

Injected into the cavities, the foam fills the space slowly, forcing its way into nooks and crannies that would be impossible to fill any other way. I made the following video a few years back and it shows slow-rise foam being used to insulate the walls of a garage that had no insulation:

Possible savings: 30 to 50 per cent depending on the current state of the walls.

#8. Install powered attic ventilation

When was the last time you stuck your head up into an attic on a sunny summer day and didn’t find it sweltering hot? Never, right? Even with loads of ventilation, attics are hot enough in summer to make upper floors difficult to cool and unnecessarily uncomfortable.

Adding a gable-mounted or roof-mounted electric fan to move hot air out can make a hot house much less stuffy in summer. Solar-powered attic ventilators are hitting the market now, too.

The only caution is the need to have sufficient vent space in the attic. There must be enough to prevent negative pressure in the attic space while the fan is running. A vent area of at least 1/200 of the attic floor area (not including the vent area of the powered fan itself) is usually enough. Double check by pulling the attic hatch back slightly while the fan is running. If you feel lots of air being drawn upwards, you need more open vent space to the outdoors.

Possible savings: 10 to 20 per cent on cooling costs, plus more comfortable upper levels.

#9. Learn about grants

Governments in many places encourage better buildings, and they’re willing to offer some of our own money back to us to make that happen. One way is grants for energy upgrades. The presence of these programs comes and goes, but there’s usually something in place to help reduce costs.

Find out about the Canada Greener Homes Grant and more

Possible savings: Many grant programs pay for 50 per cent or more on energy upgrades.

#10. Install radiant heat reflectors behind rads

Homes built before 1980 and heated with hot water usually lose way too much heat through inadequately insulated walls immediately behind hot water radiators or convectors. An independent study at the University of Waterloo shows that Novitherm Canada produces the world’s most efficient heat reflectors to solve this problem.

Scientifically designed and made of lightweight PVC with a reflective, aluminum coating on the outside, these heat reflectors stick to the wall behind rads and reflect over 93 per cent of the radiant heat back into the room, improving comfort and yielding an annual savings of 10 to 12 per cent on heating bills. The typical cost per house is $150.

Possible savings: About 10 per cent in homes built before 1980.

Energy efficiency is like anything else in life. If you want different results, you need to take different actions. Building or renovating to meet 21st-century realities requires new kinds of materials and new sets of skills marketed in new ways.

Take the time to find out exactly how you can save energy and it’ll work out better for everyone.