What does the housing crisis, a national concern, mean for Eastern Ontario? This week’s Eastern Ontario Housing Summit tackled that question, and the answers left the audience of homebuilders, planners, consultants and others with fresh insights, multiple perspectives and, more often than not, pivoting between optimism and pessimism.

Organized by the Ontario Home Builders’ Association in conjunction with several Eastern Ontario associations, the one-day housing summit featured keynote speakers and panellists who addressed three key issues — population trends, housing demands and the regional economy — in the context of a need for nearly 200,000 new homes in Eastern Ontario by 2031 as part of the Ford government’s goal of building 1.5 million homes in the province by that same year.

Economics at the housing summit

Keynote speaker Jean-François Perrault, Scotiabank’s senior vice-president and chief economist, took on the thorny issue of the economy and Eastern Ontario, looking at current conditions and what’s likely to happen in the near-term future.

While Perrault foresees interest rates falling to somewhere around three per cent within a couple of years as the Bank of Canada cuts the prime rate, he said there’s no guarantee that would happen. Assuming rates do decline, he foresees prices increasing as homebuyers, who retreated from the market during the spate of interest rate increases and the inflationary spiral of the past few years, surge back into a marketplace characterized by a “fundamental massive imbalance between supply and demand.”

With housing prices in the Greater Toronto Area (GTA) beyond the reach of many buyers and the opportunity for existing homeowners in that area to sell their homes at a substantial profit, Perrault also sees an influx of buyers to less-expensive Ottawa and surrounding small communities, putting further pressure on prices in Eastern Ontario.

All this will exacerbate the long-running affordability crisis. “It doesn’t mean prices will increase 20 or 30 per cent, but it’s hard to see how prices could improve. As a result, it’s hard to see affordability moving in any significant way. That should be the framework policymakers think about for housing going forward, to assume affordability will only get worse.”

Municipalities, he the housing summit, should consider affordability a “persistent, ongoing challenge.”

Pointing to factors like long-standing labour shortages, Perrault is pessimistic about reaching the province’s ambitious homebuilding goals by 2031. “We can’t see how that is going to happen,” he said.

At the same time, he said, quality of life and a lower cost of living can draw labour to smaller communities, giving them an advantage over cities in meeting housing demands.

Answering an audience question, he said he’s optimistic about the role that increased productivity — occasioned, for example, by factory fabrication of housing components — can play in speeding up homebuilding.

Population at the housing summit

Mike Moffatt, senior director of policy and innovation at the Smart Prosperity Institute and an assistant professor at Western University’s Ivey Business School, dove into the impact of population growth on housing demand in Eastern Ontario.

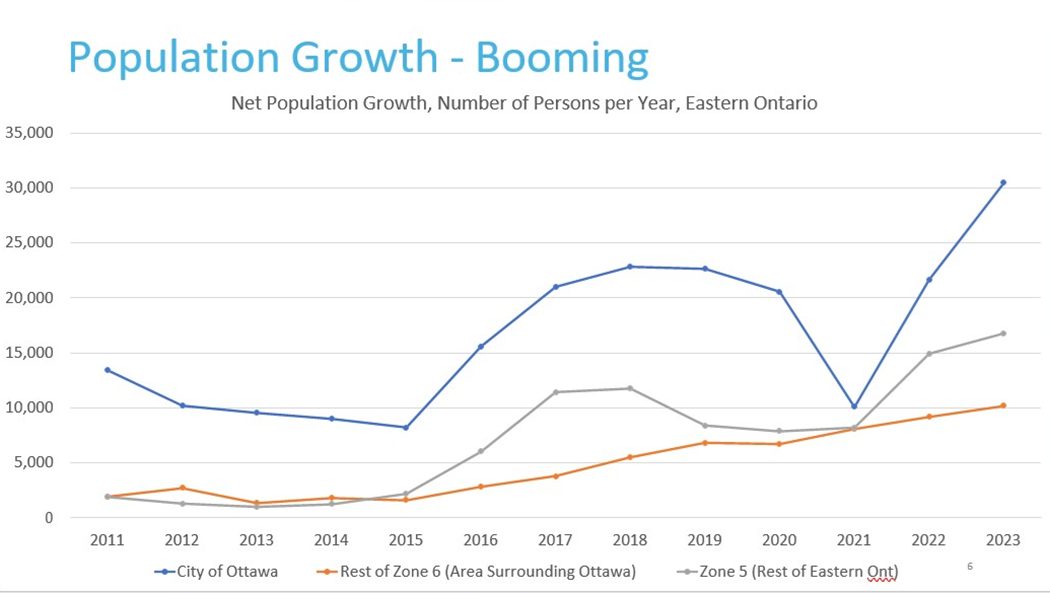

He examined three regions: the City of Ottawa; Zone 6 (the Ottawa region excluding the City of Ottawa but including Renfrew, Lanark and other areas); and Zone 5 (Northumberland, Frontenac and others).

He said Ontario needs closer to 1.7 million homes by 2031 rather than the provincial goal of 1.5 million to account for population growth, which he said has been vastly underestimated in municipalities’ official plans. In Eastern Ontario, for instance, population growth is four to six times higher than was projected in official plans a decade ago.

He also critiqued the provincial goal of 200,000 new homes for Eastern Ontario, including Ottawa. “I get a little more than that, probably closer to 250,000, but it’s in the ballpark. But these numbers assume the GTA can actually build enough to support their (housing) demands. But they can’t.” And if that drives people to Ottawa, which may not be able to meet its own goals, there’s a spillover of would-be homebuyers into other parts of Eastern Ontario, creating other problems.

“This isn’t rocket science,” he said subsequently. “This is almost a discussion of the blindingly obvious, except it doesn’t seem to inform our planning or policy decisions at all.”

Zeroing in on Ottawa, Moffatt — who came armed with no shortage of graphs and a headful of numbers — said the city is growing primarily because of immigrants (permanent residents) and international students. He told the housing summit that about half of immigrants are aged 24 to 36 and either have or want children, making them prime candidates for three-bedroom homes, including apartments. That’s a problem, he said, because we are currently building only about half as many three-bedroom homes as we did 20 years ago.

Outside Ottawa, people aged 25 to 35 with children and those aged 45 to 65 represent most of the population growth, which is coming principally from migration from other parts of the province as well as international students headed to Kingston and Peterborough. The younger cohort comprises a lot of first-time homebuyers, while the older group includes many late-career professionals.

These new arrivals are attracted by quality of life, housing attainability and the desire for more space, including room to raise children.

How to solve all these problems, including the affordability crisis?

“You have to start at development charges (the fee municipalities charge homebuilders to help pay for infrastructure) and land prices” to create affordable housing, said Moffatt. Municipalities also need to do a better job of planning for growth, improve zoning, and, at the national and provincial levels, there needs to be building code changes to make the construction of three-bedroom apartments easier.

Housing & planning for growth in smaller municipalities

Panellists in the housing summit’s two breakout sessions brought wide-ranging perspectives to housing availability, affordability and related topics in smaller Eastern Ontario municipalities like Mississippi Mills and Frontenac County.

Meredith Staveley-Watson, manager of government relations and policy for the Eastern Ontario Wardens Council, pointed to the crying need for more affordable housing in the region, including 16,000 residents awaiting rental accommodation, as well as the multi-billion-dollar infrastructure deficit the area is confronting. She also mentioned forward-looking strategies that could help alleviate a variety of problems, from Passive House construction, which reduces energy costs and greenhouse gas emissions, to the use of 3D printing technology for automated homebuilding.

Kevin Farrell, who is Frontenac’s manager of continuous improvement, spoke about communal potable water and wastewater management services to support housing growth in villages and hamlets, where such municipal infrastructure is generally non-existent.

Communal services, as opposed to individual wells and septic systems, can help increase density and reduce development time while also better safeguarding the environment through regular inspections and maintenance. Such services also have potential for smaller apartment projects and commercial developments.

Other panellists included Christa Lowry, mayor of Mississippi Mills, where population is expected to double within the next decade.

Part of a question-and-answer session moderated by Pierre Dufresne, who is president of the Lanark-Leeds Home Builders’ Association, Lowry said her municipality is handling some of the many challenges of growth through public education and actively involving the community in policy development and planning.

“We’re hardwired not to change, so we have to bear that in mind as we do this,” she said at one point. “Engaging (people) in a meaningful way helps them to understand the development process.”

She also noted that new housing types, including back-to-back townhomes, and more purpose-built rental apartments will help meet the coming explosion in housing demand.

Other panellists in the housing summit breakout session spoke about everything from the coming need for expanded waste management strategies as populations grow to fresh approaches to municipal planning.

Eric Withers, deputy chief administrative officer and director of development, environment and infrastructure for Renfrew, said he wants to protect the character of his community and cultural resources for future generations. At the same time, he sees the need to balance market forces and the public interest.

“We have to make some value-based decisions when it comes to this target we have to hit of building 1.5 million homes. Do we need to be protecting every brick, bird and turtle that we come across?” he asked. “How we’ve been approaching planning and policy development, there’s just been a disconnect between the policy objectives and how we craft the policy and what makes a realistic (outcome).”

Housing & economic development in larger municipalities

In another set of breakout sessions at the housing summit, panellists discussed the pressures on housing in cities such as Cornwall, Kingston and Peterborough, how that affects economic development and ways they are working to overcome the challenges.

These mid-sized municipalities share many of the same issues as metropolitan areas like Ottawa, including when it comes to affordable housing, but they also have other challenges that they share as a group, such as difficulty replacing retiring municipal staff quickly enough to keep the development process moving, and a propensity for single-family homes.

“What’s lacking for the downsizers and the newcomers to the market is a variety of housing products that Ottawa has always had,” said Miguel Tremblay of Fotenn Planning and Design.

In these municipalities, that has resulted in a push to increase both density and height — much like we’re seeing in Ottawa — with high-rises now popping up in the likes of Kingston and Rockland.

“People have got to understand that the profile of the skyline is going to change,” said Peterborough mayor Jeff Leal.

Another common issue is the correlation between the ability to attract businesses to these cities with the ability to then house incoming workers. Eastern Ontario cities are keen to bring economic investment to their municipalities, but “today, when we talk about investment, we’re talking about expansion of housing stock to accommodate that investment,” said Bob Peters, manager at Cornwall Economic Development.

Creative solutions such as overcoming a staff shortage by having a building code official who works for a region rather than just one municipality, or shifting the focus of city planning to be ahead of the supply need rather than reacting to it to limit red tape will help, said Mathieu Fleury, a former Ottawa councillor who is now chief administrative officer for the City of Cornwall, but there are still challenges.

He also sees opportunity in having what he calls “outside” developers from Ottawa or the GTA come into surrounding cities with fresh ideas on height and density.

Along with those fresh ideas, there’s a push to court developers, much as a city would court business, touting lower-cost land, typically a faster development approval process and lower development charges, said Peters.

Rhonda Keenan, who is president and CEO of Peterborough and the Kawarthas Economic Development, noted that they are taking a multi-faceted approach to housing issues that includes spearheading programs to encourage people to get into the trades and looking at innovation such as 3D printing to build homes better and faster.

Kingston is also looking at a multi-faceted approach, said Shelley Hirstwood, director of business development at Invest Kingston. That includes considering a significant urban boundary expansion, innovation in building and looking at pairing housing with industry so that you could have homes on an industrial property.

Ultimately, when it comes to housing solutions, we need to take a systematic approach, said Royce Fu, acting manager of policy planning at the City of Ottawa. “Who are the actors in housing construction, what are their roles, and what can they do? … We need to be looking outside the box.”

We also need to streamline the approval process, incentivize and use reductions in development charges, said Tremblay, with Peterborough mayor Leal adding that we need to set benchmarks for the approval process timeline. “If you don’t have those benchmarks, you’re not driving the process.”

Encapsulating the day, Fleury noted that the value of a housing summit like this is to bring so many parties to one spot to ask: “How does the eastern region work together?”